The Ford Explorer was effectively the official car of the suburbs twenty years ago, as Americans embraced the roominess and practicality of the best-selling SUV.

But compared to the engines beneath the hoods of today’s rides, that Explorer’s powerplant was practically an antique.

No, we aren’t driving the atomic/turbine/hydrogen fuel cell/battery electric dream cars that have remained elusively over the horizon for most drivers. Instead, we have vastly modernized internal combustion gasoline engines that are smaller and more efficient while providing more power than ever.

“These engines have changed slowly over time so it kind of sneaks up on you so you don’t realize how much they’ve improved,” noted David Turcotte, Director of Technology & Product Development for Valvoline.

“They’re much smaller,” he elaborated. “A four-cylinder might produce as much power as a V8 did 20 years ago. The fuel mileage has practically doubled and the engines are much smaller.”

Indeed, the 2018 Explorer is available with a turbocharged, direct fuel-injected 2.3-liter four-cylinder engine rated at 280 horsepower and 310 lb.-ft. of torque. The 1998 Explorer’s 5.0-liter V8 engine produced an inferior 215 horsepower and 288 lb.-ft. of torque under a more generous rating system in use at that time.

Meanwhile, the new Explorer is rated at 19 mpg in city driving and 27 mpg on the highway according to the EPA. Using the EPA’s older, more lenient scoring system that inflated efficiency by a couple mpg, the V8 ’98 Explorer scored 12 mpg city and 17 mpg highway.

The thirsty old engine was a cast iron V8 with pushrod-actuated valves and port fuel injection. Its origin was Ford’s very first small block V8, which debuted in 1962.

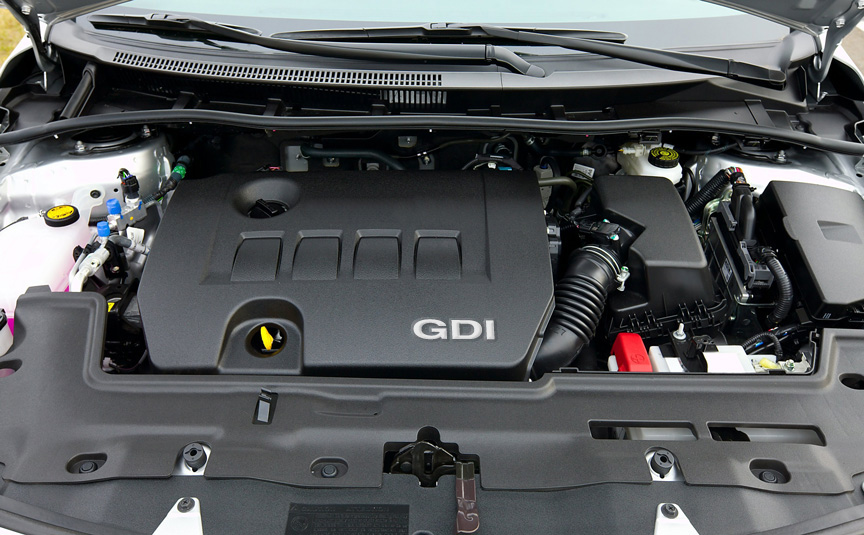

Today’s model uses Ford’s “EcoBoost” 2.3-liter aluminum four-cylinder with advanced turbocharger design and direct fuel injection. Valves are operated by a pair of overhead camshafts that provide variable timing of the intake and exhaust valves independently of one another.

It really does seem miraculous, doesn’t it? But there are tradeoffs for this improved efficiency. For example, direct-injected engines are proving prone to troublesome carbon build-up on their intake valves. This results because the gasoline is shot straight into the combustion chamber in engines, while it has traditionally gone into the intake port, where it washes over the intake valves on the way to the combustion chamber.

Fortunately, Valvoline offers Modern Engine Full Synthetic oil, which is engineered to reduce the problem of oil leaking and caking onto the unwashed intake valves of direct-injected engines, Turcotte said.

Modern small-displacement engines have many more parts, made and assembled to extremely precise standards and tolerances, which results in a system that is more sensitive to problems than the lazy old inefficient, but tolerant, V8s.

Additionally, just as we get hot and sweaty when working hard, these hard-working, smaller-displacement engines produce a lot more heat than the old engines. “That is not for free,” observed Turcotte. “It is running much, much hotter. “

That heat creates its own challenges, as it is harder on all under hood components and breaks down lubrication faster than the cooler-running engines did.

This makes oil change intervals more critical than ever, as this harsh environment hastens the breakdown in oil thickness, Turcotte reports. These are exactly the problems Modern Engine Full Synthetic is designed to combat.

Many of the remaining V8 and some V6 engines employ cylinder deactivation, which lets them run on few cylinders when the power demand is lower. This can also contribute to issues such as fouled sparked plugs from the cylinders that are going through the motions without actually firing all of the time, he said.

Spark plugs are typically intended to last 30,000 to 100,000 miles without replacement. However, the reality is that leaving factory plugs in the engine so long may be a bad idea.

“Mechanics have told me if you don’t take them out sooner, say by 50,000 miles, you might not get them all out later without breaking them. And it’s always a good idea to check the gap,” Turcotte warns. You could simply remove the old plugs, check the gap and possibly coat their threads with an anti-seize compound, if recommended, to prevent them from getting stuck, but replacements are inexpensive, so once the old spark plugs are out, it is surely worthwhile to install new ones.

Variable valve timing technology adjusts the camshaft’s rotational position, to make valve opening ideal for the engine speed and load. The cam timing solenoid that performs this chore can go bad, producing a rough idle and illuminating the check engine light.

The good news is that the part is relatively inexpensive and on engines like the popular General Motors Ecotec four-cylinder, is easier to access and replace than changing spark plugs, so it’s an easy DIY fix for less than $100.

Another difference between traditional V8 engines and most four-cylinders is the smaller engines’ use of a rubber timing belt to operate the valves in place of a steel timing chain.

Belts are lighter, cheaper, and quieter, but of course, rubber ages and hardens. These belts typically need to be changed at 60,000-mile intervals.

In the best case, if it breaks while you are driving the engine will instantly stop running, potentially stranding you in the middle of a busy highway.

Worst case scenario, if your car’s engine is an “interference” design, the still-moving pistons will crash into the suddenly stationary open valves, bending them in the process. Now your repairs have gotten exponentially more expensive.

Carmakers are looking at more advanced engine coolants to help protect modern hot-blooded engines, reports Turcotte, so we will soon have more new maintenance information to consider. Until then it seems like regular changes of high-quality oil like Valvoline Modern Engine Full Synthetic, replacement of spark plugs, and timely timing belt replacement are prudent ways to care for your car’s increasingly sophisticated, powerful and efficient power source.

Dan Carney

Dan Carney